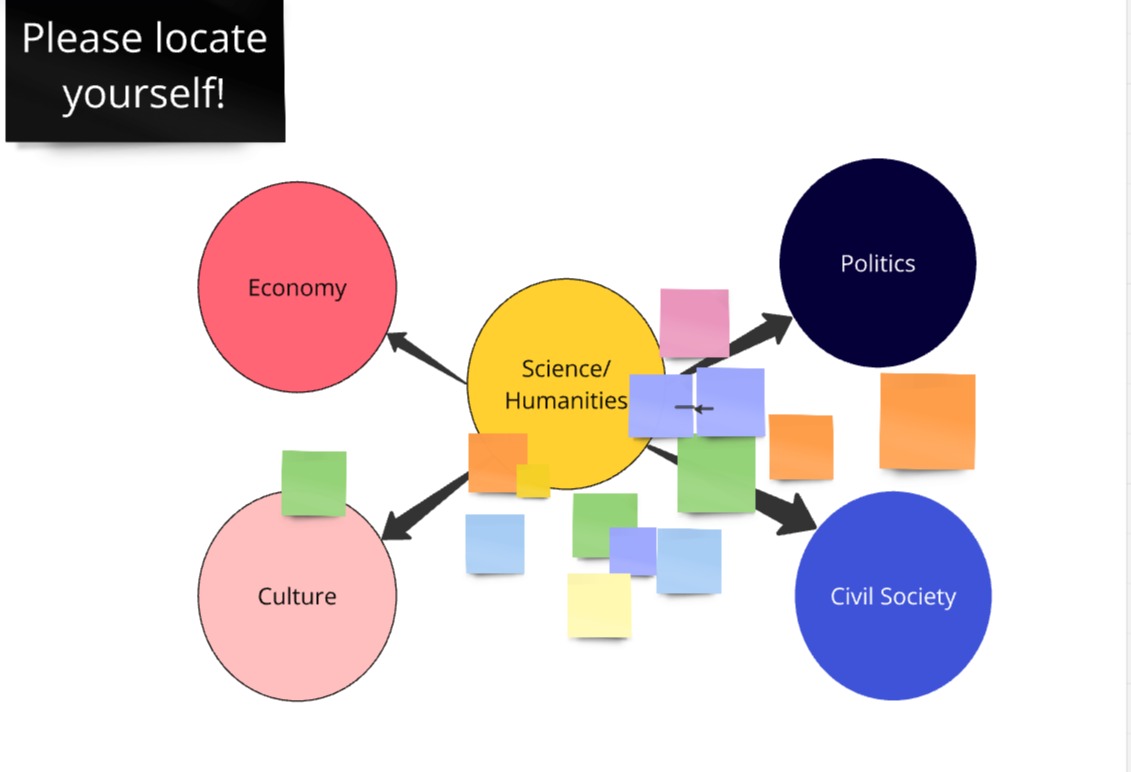

As defined by scholars like Susan Strega and Leslie Brown, activist research is distinct from participatory methods in that it prioritises ethical co-production of knowledge and transformative action (Strega & Brown, 2015). The workshop’s goal was to explore and share how both researchers and activists can foster equitable collaboration and address the ethical complexities inherent in such work.

While activist research is always situated, it also follows global demands that allow it to intersect with the concerns, struggles and critiques of other cases that one is not directly involved in. Activist researchers aim to achieve particular situated goals that are oriented towards larger claims to power, such as improving the practice of justice or labour conditions. At the same time, activist research is embedded in old and new forms of controversy, involving the continuation of hierarchies between activists and scholars or the appropriation of struggles and their vocabularies. Activist research is thus an approach that goes beyond participation, demanding more resources for and analysis of ongoing cooperations between research and political struggles.

By critically engaging with concepts of activist research, the workshop aimed to move beyond traditional science communication with its focus on informing. Instead, it emphasised collaborative knowledge production with issue publics, such as mobility justice activists in the project B09 – “Bicycle Media” and civil society actors from Ukraine in the framework of the project P06 – “War Sensing”, both of which focus on working with activists.

These issues were addressed by two keynote speakers on the first day. Giancarlo Fiorella, the Head of Research from Bellingcat, elaborated on the potential of open science and open-source investigations to democratise research and blur the line between the researcher and the public, allowing for broader public participation in creating different forms of knowledge. Sevda Can Arslan, a media scholar from the University of Paderborn, made a strong case for the need to foster dialogue between academia and society in order to create knowledge that resonates beyond institutional boundaries. She also reflected on the tensions between applied research, public science, and science communication.

On the second day, the workshop was divided into three sessions, each looking at activist research from the perspective of case studies: 1. feminist archiving and editing practices, 2. mapping, and 3. collaborating with healthcare workers during the war in Ukraine. The case focus is important here because it illustrates how activist research is always embedded in particular communities and requires sustained attention in order to change the situation on the ground.

1

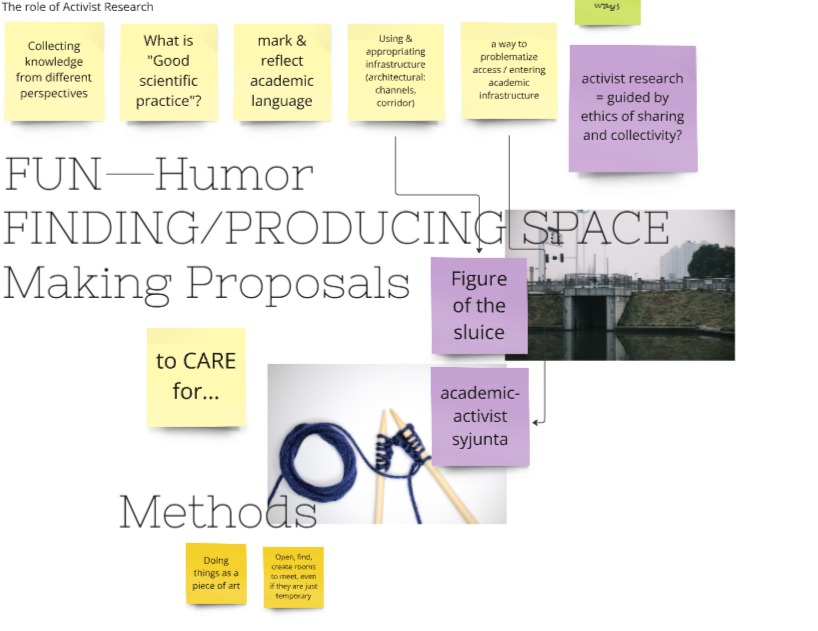

Chris Regn and *durbahn (bildwechsel/Who writes his_tory) hosted a session on feminist archiving and editing of Wikipedia, both of which emphasised the principles of inclusivity and shared knowledge production. Their activist practice aims to disrupt traditional archival practices by prioritising alternative, less represented narratives and amplifying voices that have been historically excluded from dominant historical accounts. Chris Regn and *durbahn illustrated how such archiving and editing practices challenge traditional epistemological hierarchies and call for a reflexive approach that acknowledges the researcher’s situatedness and positionality in knowledge production. A dynamic and lively discussion unfolded on the subject of integrating feminist archiving and web-editing methodologies into academic research practices. Inspired by practices such as Sweden’s Syjunta—a gathering of women to knit and talk—participants emphasised the value of creating alternative spaces for collaboration. Changing the physical environment was noted as a way of encouraging different forms of interaction. Two compelling metaphors emerged from this conversation: the sluice, representing the facilitation of collective practices, and weaving/knitting, symbolising the interweaving of diverse threads of knowledge and collaboration. These metaphors highlighted that activist research thrives on an ethic of sharing and collectivity, reshaping how knowledge is produced and disseminated to empower communities and challenge hierarchical norms.

2

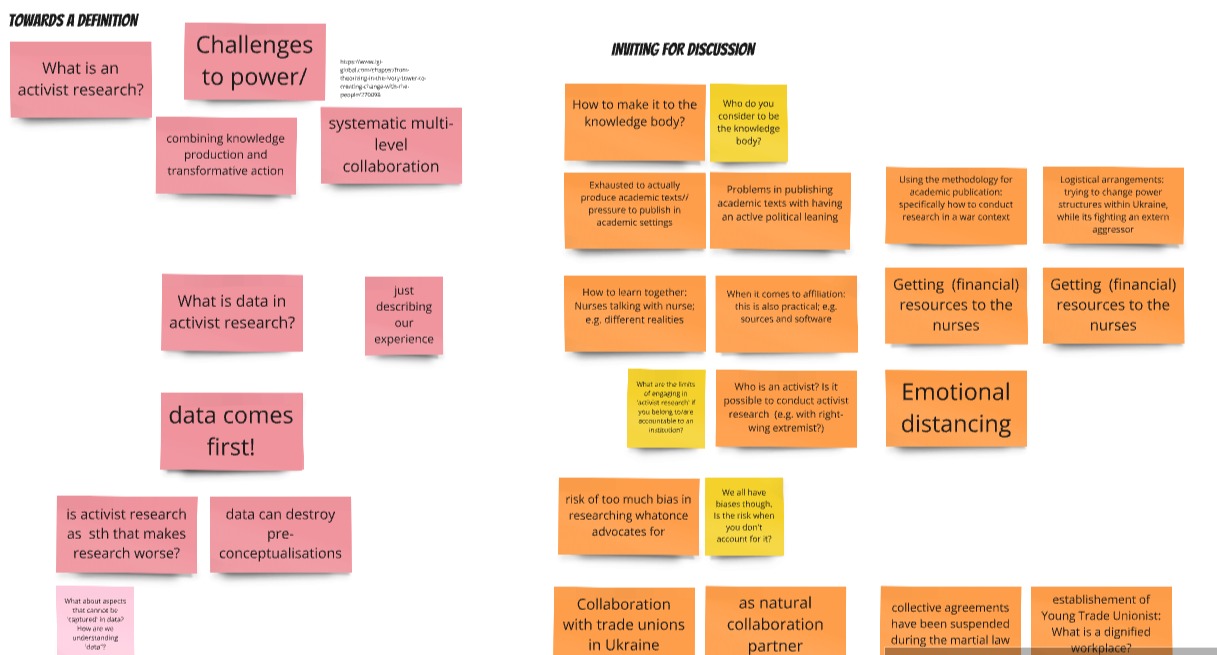

The second session, led by Paul Schweizer (Kollektiv Orangotango), focused on collective mapping as a both research practice and a medium of cooperation practice. Examples from Indigenous land claims, urban housing crises, and pandemic-era mutual aid efforts demonstrated the dual nature of mapping in activism. Paul Schweizer identified key insights critical to the ethical use of mapping in activist contexts, distinguishing between internal mapping used as a community strategy and external mapping designed for public advocacy. He argues for mapping as a tool for activist issues. He also emphasised that research findings need be tailored to resonate with diverse audiences, ranging from legal courts to social media platforms, in order to maximise accessibility and impact. The discussion also highlighted the double-edged nature of mapping, where maps can empower communities, but also can expose vulnerable groups to risks. This prompted an examination of the necessity of discerning when mapping is not the optimal approach. The significance of reflexivity and ethical awareness was underscored, with researchers being urged to prioritise community safety and adopt context-sensitive practices to achieve a balance between the empowering potential of mapping and the ethical responsibilities it entails.

3

In a third session, Tasha Lomonosova (ZOiS), presented findings and insights from her collaborative research on nurses’ labor during wartime in Ukraine, exemplifying how activist research combines knowledge production with transformative action aimed at addressing and resolving social inequalities. Nurses from different parts in Ukraine actively participated in every stage of the research process, including conducting interviews with fellow nurses. This approach aimed to address and reduce power imbalances both within healthcare systems and between academic researchers and practising nurses who lacked formal research training. Tasha Lomonosova’s session highlighted the challenges of conducting activist research in wartime, such as the unequal power dynamics between Ukrainian and international collaborators, but also the resilience of collaborative research practices as transformative under conditions of war. Participants discussed practical dilemmas, such as how to navigate ideological differences within partner organisations and how to handle sensitive data that may conflict with activist goals, emphasising the need for researchers to be not only reflexive but also flexible. A key concern was to avoid the tendency to treat grassroots groups as monolithic entities, and instead to recognise their diversity and internal complexity.

Overall, the workshop provided a space to discuss the intersection of different approaches to activist research, including its practices, methods and ethical concerns, each drawing on specific cases. As organisers of the workshop, we want to thank everyone who joined this workshop for their mutual support and collaboration.