Cross Community Learning plays a major role in IT design. Concepts such as participatory and co-design focus on interdisciplinary learning relationships with building up spaces where mutual learning at eye level is possible. With the entry of digital tools into all areas of life and also to user groups that until recently were not considered as target groups of IT production, e.g. people with disabilities, children or older people, a further development of a systematic understanding of learning, IT design processes, and the social space both is situated in is necessary.

„When the data is created from you, about you by you, then you should have the right to access and use that data above and beyond anybody else“ – Annika Wolff

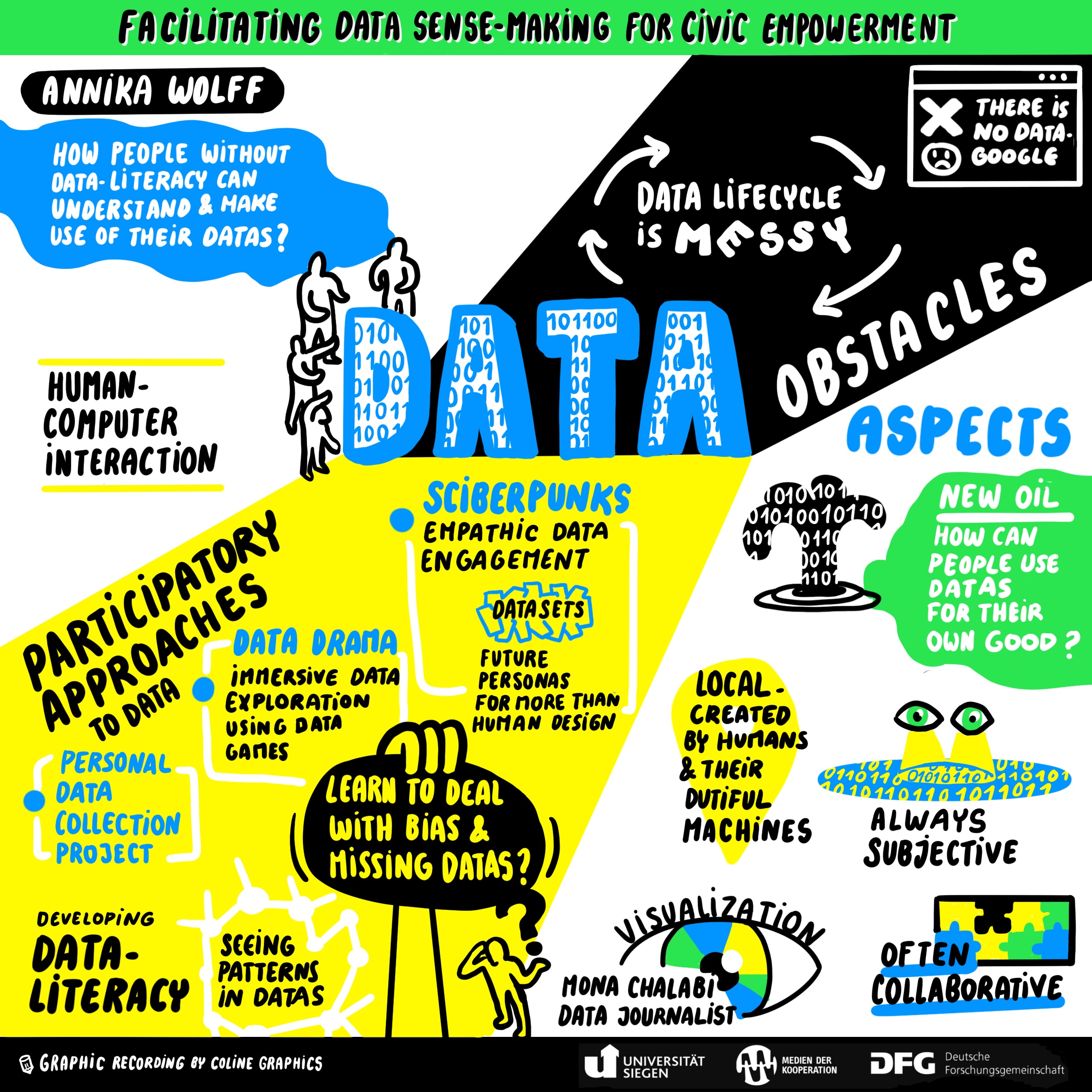

Annika Wolff spoke on this topic with the focus ‚Facilitating Data Sense-Making for Civic Empowerment‘. Behind the strong title lies a local, situational understanding of data and data practices, which are subjectively produced by human and non-human actors against the background of their respective contexts and result in further interaction between humans, machines and the data stream. Emotion emerges from this interaction. Data therefore has a collaborative nature that connects actors. Whether this connection is based on consensus cannot be assumed, however, according to Wolff.

Consensus presupposes a common understanding. Data must therefore be universally interpreted in the same way, but this often proves difficult in practice, because within our data there is often messiness in form of errors and lack of information.

Within the common understanding process, further errors can also occur. Background: Marginalized and/or vulnerable target groups in particular, who have been largely ignored in the development of digital technologies to date, struggle in their understanding of data and/or are underrepresented in existing data, e.g. due to a lack of accessibility to technology or integration into the design process.

Starting from the problem, collecting and processing data to achieve a solution, whether the problem is of a societal, target group-oriented or individual nature, is therefore always a challenge. However, it is even more difficult to localize the problem from the existing data set and then generate an adequate solution. The collection of similar data, which is referred to as the ‚personal data collection principle‘, can support this. This principle opens a door that makes especially those heard who usually cannot speak for themselves. Nevertheless, data availability does not automatically mean data justice, an individual or target group-based problem that remains as a societal challenge.

How can we adequately address this dilemma?

Against this background, Wolff describes local-oriented and human-centred methods that promote empathy and empowerment of the civilian population by incorporating artistic aspects and focusing on the promotion of media competence via data. The so-called ‚data drama‘, which she cites as an example, allows for immersive data exploration through data games, where the dramaturgical framework functions as an alternative way of making sense of data, which is generated in interactive, collaborative contexts.

Open questions are those concerning the adequate communication of the benefits of data to various target groups and, in this respect, those concerning the first steps towards joint data exploration.

„If we don’t have good data we can’t go on with Cross Cultural Learning.” – Jennifer Rode

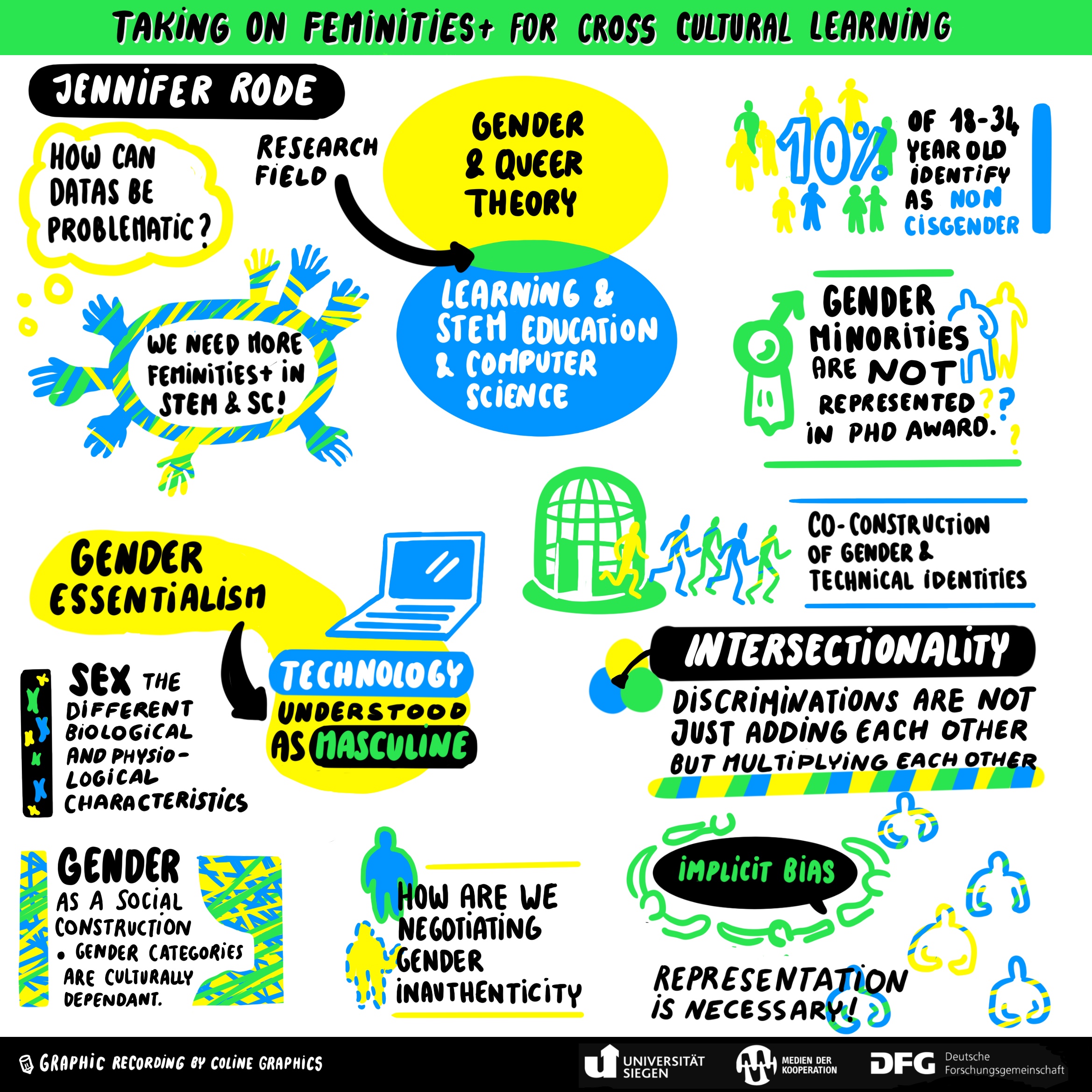

Cross Cultural Learning is an important aspect of Cross Community Learning. Jennifer Rode deepened this basis of shared knowledge culture in her contribution ‚Taking on Femininities+ for Cross Cultural Learning‘, in which she focused on the participation of minorities in the STEM sciences. While the call so far has been for more women and thus equality within the commonly held binary system, Rode argues for moving beyond this familiar and limited framework, which so far excludes the current 10% of people who identify as non-cisgender.

The social construction of systematic binary education within our societies not only creates a very simplified image of gender, but is at the same time, according to Rode, tied to a technical identity. However, societies differ culturally in this respect. A transformation towards Cross Cultural Learning is thus also linked to a transformation within the framework of social inclusion; value systems must be opened up and expanded to include those that have so far remained unconsidered. Only such an integration and recognition of multiple perspectives will ultimately enable the inclusion of equal values in technical design, which shapes lives worldwide. Such equality of diverse genders and cultural backgrounds thus reduces the inherent bias in our current technologies and thus data practices and data streams and therefore reduces the subliminal racism fed into technical artefacts that we have to deal with today in a self-critical and self-reflective way against the background of Western, masculine and white privilege.

On a social level, such an opening through inclusion gives authenticity to those marginalized groups who have so far been subjected to the mantra of gender-oriented performance, especially in professional contexts. It also creates equal participation at all levels and enables the use of one’s own voice in private and public spaces. Ultimately, everyone benefits from this, including the male gender, according to Rode, which until now, exposed to toxic masculinity, has also been forced to perform.

The guiding principle for further research and practical implementation of ethically justifiable IT design is therefore:

„Embrace femininities+ and intersecionality as starting points for design and theoretical framework to examine the bi-directional shaping of society and technology.“ – Jennifer Rode

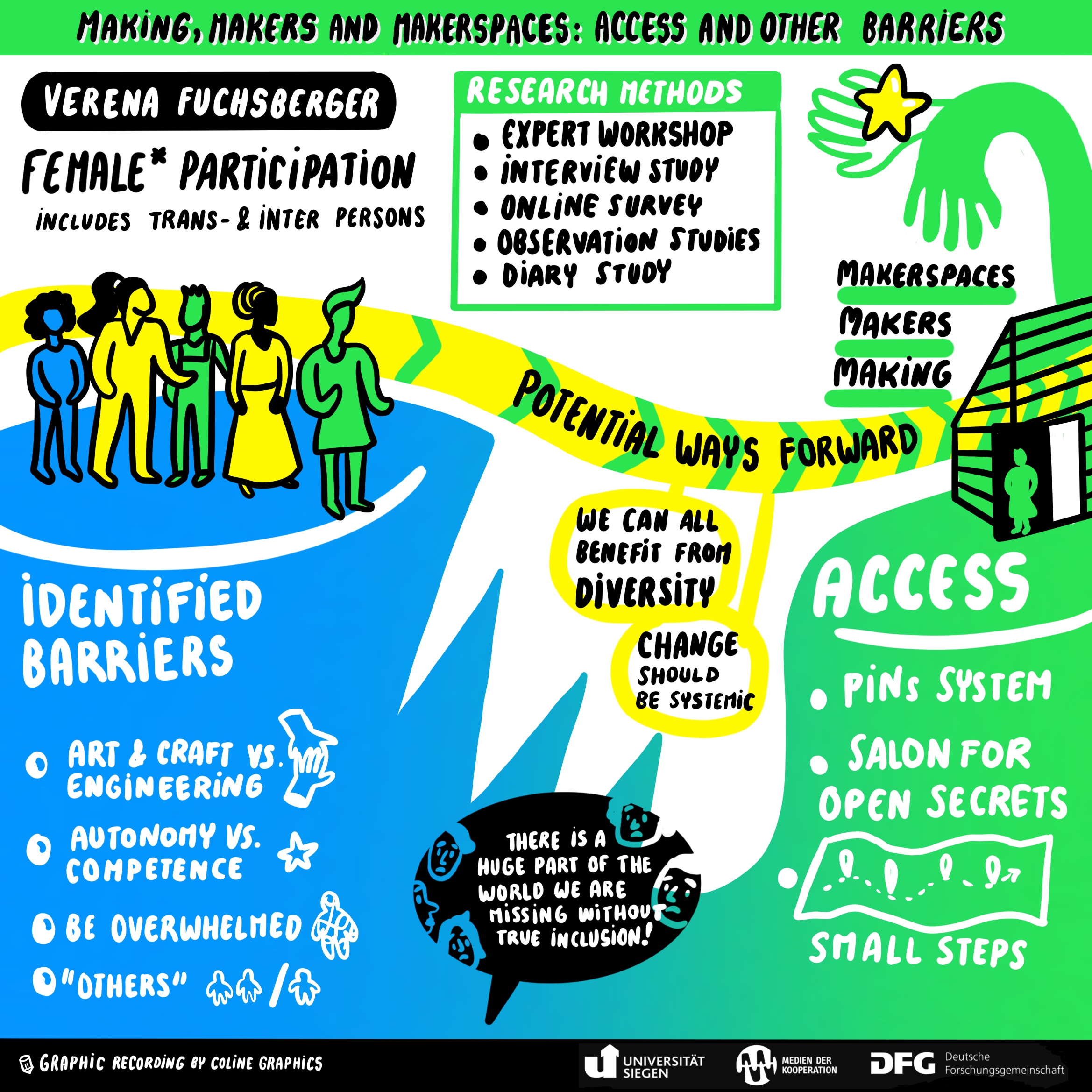

A practical example of cross-cultural learning against the background of such a transformative process was given by Verena Fuchsberger with the title ‚Making, Makers and Makerspaces: Access and Other Barriers‘. By integrating female engagement within this field, the previous trend of primarily male presence in makerspaces is breached. Another important factor is education. Makerspaces can be understood as educational spaces that, contrary to their current nature, should not be homogeneous, but a safe, social space for people with different levels of education, where everyone can be both teacher and student. However, according to Fuchsberger, this wishful thinking is sometimes accompanied by barriers. They include the overlapping of subject and skill areas, consisting of arts and crafts and engineering. As Jennifer Rode pointed out, our technical identity is tied to our gender identity. In practice, this creates a perception for many people that they may not be technically skilled, or even a fear of failure. This attribution of competence or lack thereof can further lead to an inner resistance that prevents participation in order to preserve one’s autonomy. During participation, such a feeling can lead to a sense of being overwhelmed. The negative influence of one’s own socialised peer group, which warns of such barriers and further negative experiences or emotions in advance, has also been identified.

What is needed are new role models. According to Fuchsberger, pioneers within male-dominated spheres, such as in the makerspace, are necessary to act as door openers and lower fears and barriers. Already existing or increasing diversity must be made more visible against this background.

„One day, maybe, we will ask: ‚What was the gender gap?‘ and ‚How was it solved?‘ and ‚Why did it even exist?” – Verena Fuchsberger

On the way to such a visionary future of equality, Cross Community Learning against the background of a common understanding of data, in new safe social spaces, represents the cornerstone, as does its theoretical foundation, which is based on a change in values within science, which, as it were, carries such a change back into society via technical design and helps to reshape socialisation.

Gerhard Fischer took a closer look at the future in his keynote ‚The Future of Learning and Digital Media. Exploiting and Supporting the Synergy between Renaissance Scholars and Renaissance Communities‘.

„Collaboration is key as the power of the unaided individual human mind is limited.“ – Gerhard Fischer

This orientation in the here and now is accompanied by many questions, e.g.: What role can technology play in this? What can meaningful knowledge management look like? or How do we move from a culture of ‚having to learn‘ to one of ‚wanting to learn‘?

With reference to antiquity, Fischer points to the importance of external forms of documents that have always carried the knowledge of mankind to ensure its collective survival. Modernity and its technical designs, however, have led us into a dilemma. Thus, in addition to truths, negative effects are now hidden in our knowledge tools, such as information overload or filter bubbles. In addition, we are struggling today with Wicked Problems of global proportions that are bringing our established systems and familiar structures to their knees and making change inevitable. Topics such as technology development, participation and learning are coming to the fore. Keywords here are Cross Community Learning, Cross Cultural Learning, Situated Learning and Life Long Learning. Learning is key. Individual attributes as well as those of the respective context come to the forefront of research and development, roles of teacher and learner become increasingly blurred, and rightly so, because:

„Intelligence is distributed across minds, across cultures.“ – Gerhard Fischer

Traditional learning systems, into which technology is incorporated, will compete in the future with such – still visionary – co-evolution of people, knowledge and technology, which form a new, shared learning space. Covid-19 can be interpreted as a push into such a development, Fischer says. How do we design learning spaces under these conditions and henceforth to turn the compulsion for transformation into one of added value?

Fischer speaks here of Renaissance Scholars or Renaissance Communities because we are in a time of transition. Just as the Renaissance, which describes the transition from the Middle Ages to Modern times, was characterised by a revival of cultural achievements of antiquity, we need to revive cultural achievements to find our way back to the collective intelligence, which is composed of diverse forms of knowledge and culture. The very impossibility of a perpetual articulation of specific problems makes inclusion of affected persons or groups in participatory learning processes indispensable.

„None of us is as smart as all of us.“ – Gerhard Fischer

In addition to cultural knowledge, other different forms of knowledge are waiting on the path of transformation towards a collective knowledge structure, e.g. professional knowledge, technical skills or media competence. A model for the Renaissance of the 21st century therefore aims at sharing knowledge and learning from each other, which is only possible in open, participatory learning spaces. This is where common ground must be established. A legitimate question here is:

How do we move from a competitive society to one that is open-minded and shares its knowledge openly?

Fischer refers to the so-called Fish-Scale Model (Campbell 1969): „collective comprehensiveness through overlapping patterns of unique narrowness“.

A first step is to promote interaction and communication. This is especially possible at interdisciplinary interfaces. Creating common ground through shared knowledge is fundamental here, with technological artefacts – boundary objects – playing an essential role in supporting the process of externalising ideas that support shared understanding across spatial, temporal, conceptual and technical gaps. The intertwining of Renaissance Scholars and Renaissance Communities is seminal against this backdrop, with individuality and its imprint in particular making a difference.

Who designs time and its use?

On the way to the transformation described above, so-called meta-design is becoming more and more important: participatory design for designers, not exclusively for users, or the latter should also become a designer representative of the entire user group and help shape future social and digital practices.

A second model as a possible anchor point for the development towards Renaissance Communities, to which Fischer refers, is SER (Seeding, Evolutionary Growth, Reseeding). Here, the user as designer is assigned a leading role, especially in the second phase, of Evolutionary Growth, as he or she takes the lead completely independently of the professional designer, i.e. he or she is empowered to drive development autonomously during this time.

The empowerment for this comes from the development of supporting socio-technical environments, which are shaped by Communities of Learning (CoL) that come together against the background of common interests. In order to pool knowledge on a large scale, data-oriented approaches make sense despite all the challenges, e.g. information overload or data manipulation. They create common ground while taking validity into account. But caution is advised:

„Often we value what we measure. Instead, we should measure what we value.“ – Gerhard Fischer

Research questions that follow on from this are: What data do we have? What problems can this data address? What problems do learners have? and What data are needed?

In conclusion, it can be said that against this backdrop, at the vertex between downfall and new beginning – in the dawn of a new Renaissance, modernity has a new mantra to internalize:

„The future is not out there to be discovered. The future has to be invented and designed. – Gerhard Fischer

What is and remains important is the question of who. Who is currently shaping the future and who should?

Further information on our referees:

Annika Wolff

Background & research interests:

Annika Wolff is an assistant professor whose research is in the newly emerging field of human-data interaction, at the intersection between complex data, machine and human learning. Her research focuses on engaging people with data, such as from smart cities, and in supporting non-experts in designing products and services that use data. She has expertise in using inquiry-based methods and co-creation, in developing applications of data science and in the use of tangibles, creativity and games to support learning. She has previously led work in developing and piloting new methods for teaching data literacy skills in UK primary and secondary schools and in understanding how open data can be utilized in education. She has many years of experience working within UK and European funded projects, combining applications of data science to human understanding. She has published in a number of international journals and is an active member of research communities related to community-based innovation and HCI.

More information:

https://research.lut.fi/converis/portal/detail/Person/9873617?auxfun=&lang=en_GB

Jennifer Rode

The speaker about her research interests:

“My research lies in the areas of Human-Computer Interaction and Ubiquitous Computing. I am deeply committed to understanding why technology is so empowering to some and for others it is the foundation for exclusion. My work examines the values of technological utopianism and how those values influence the user-centered design process. Ultimately, I look at how, and under what circumstances, individuals choose to use technology. Consequently, my work explores areas in which the experiences of both enthusiasts and technophobes overlap. This makes technology in the home especially relevant as it is a primary environment in which we socialize children in socially approved attitudes towards technology. My research looks at how gender is key to the ways technology is both perceived and used. Further, it looks reflectively at the design process to see how our biases and practices shape the artifacts we design.”

More information:

http://www.jenniferarode.com/Jennifer_Ann_Rode_CV2017.pdf

Verena Fuchsberger

Background & research interests:

Verena Fuchsberger is Postdoc at the Center for Human-Computer Interaction, University of Salzburg. She has completed her Master’s Degree in Educational Sciences and Psychology at the University of Innsbruck and finished her PhD in HCI at the University of Salzburg in 2015. In her research, Verena focuses on the agency of human and non-human actors in HCI and interaction design, i.e., the relations and associations between individuals (users, but also non-users, designers), materials and digital-physical artefacts. In particular, she is interested in the hybrid materiality of interactions as it occurs in different domains, contexts, and situations.

More information:

https://hci.sbg.ac.at/person/fuchsberger/

Gerhard Fischer

The speaker about himself:

“I am a Professor Adjunct and Professor Emeritus of in the Department of Computer Science, a Fellow of the Institute of Cognitive Science, and the Director of the Center for Lifelong Learning and Design (L3D) at the University of Colorado, Boulder. I am a member of the Computer Human Interaction Academy (CHI; 2007), a Fellow of the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM; 2009), and a recipient of the RIGO Award of ACM-SIGDOC (2012). In 2015, I was awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. My research interests include: new conceptual frameworks and new media for learning, working, and collaborating, human-centered computing, and design. My recent work is centered on quality of life in the digital age, social creativity, meta-design, cultures of participation, design trade-offs, and rich landscapes for learning (including MOOCs). You can find out more about my work by clicking on the respective menu entries for: Publications, Reports and Presentations, Recent Courses, Major Research Projects, and Ph.D. Graduates.”

More information:

https://l3d.cs.colorado.edu/wordpress/people/home-folders/gerhard-fischers-home-page/